Member-only story

The Most Influential Theory of Modern Painting

How Clement Greenberg defined the work of Monet, Cezanne and other modern painters

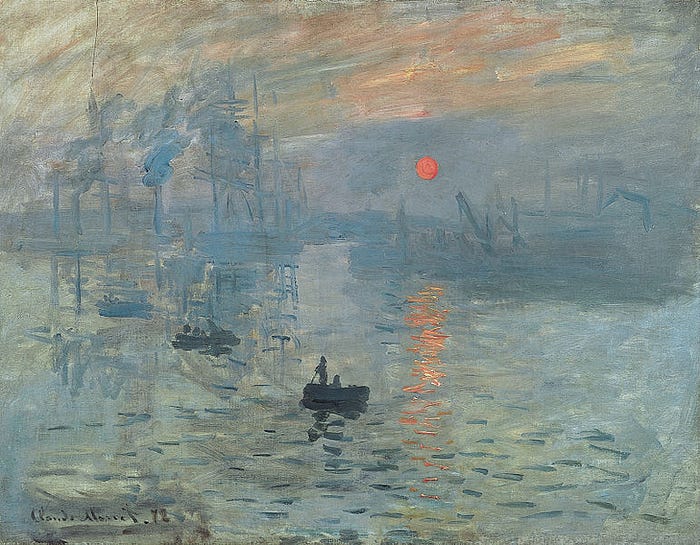

It was the modern painters who first grabbed my attention when I began learning about the history of art. Paintings by Claude Monet and Paul Cezanne, and not long after, the abstract works of Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky.

I was fascinated by them, perhaps because I was also learning how to paint myself and I could see in these works of art something open and explicit about their technique. They didn’t have the illusionistic grandeur of an Old Master. They were made with loose, tangible brush marks, which meant you could see them as objects made by real people with whom you could feel a direct relationship.

Some years later, I came across the writings of Clement Greenberg — one of the most influential art critics of the twentieth century. His famous 1961 essay Modernist Painting, explores the nature of modern painting and distills its essence into a single theory.

To give a brief summary, Greenberg argued that the hallmark of modern painting was the recognition of its own inherent properties, those of flatness (being painted onto a canvas) and of being made up of actual pigments of coloured paint. In one sense, Greenberg saw these as limiting factors. But when artists explore them explicitly — as he thought modern painters did — then these physical and material limitations became positive factors in their own right.

What did Greenberg mean by this claim, that the key attribute of modern painting was in its willingness to examine its own limitations?

Using an example such as the painter Édouard Manet, Greenberg argued that he made his pictures with a “frankness” about the surfaces they were painted on. Manet refused to go to great lengths to represent physical reality precisely. He didn’t disguise the fact that he was painting a picture, with paints and brushes, on a flat surface. Instead, he happily drew the viewer’s attention to the visual experience of the work, the tactile quality of the brush marks, made with paint — as Greenberg put it — “that came from pots and tubes.”